Dumber than fiction

How sci-fi got AI all wrong

I’ve loved science fiction for as long as I can remember. It probably started with Animorphs, a 90s sci-fi children’s series, which captivated me so intensely that I chose to stay inside and read it at recess instead of playing with friends. Despite having a mind that is usually incapable of recalling granular details from pop culture products (a trait which makes me a terrible trivia teammate), there are details from sci-fi books and movies that I saw or read just once in the 90s and 00s that stick with me even now: Jonas’s reaction to his schoolmates playing a game of ‘war’ in The Giver; billboards advertising assisted suicide in Children of Men; Ethan Hawke running on a treadmill and managing to fake a healthy heart rate in Gattaca; the wide-brimmed hat that Jodie Foster wears while listening for evidence of alien intelligence in Contact.

Sometimes friends and family, humoring me, have asked why I love the genre so much. I’ve always floundered when asked this question, but typically say some version of: I like the way that it makes us reflect on how we live now, holding a mirror up to our society, showing us the good, bad, and weird ways that things might turn out if we keep going the way that we are.

Though Black Mirror has been disappointing in recent seasons, some of the earlier episodes did this astonishingly well. The episode “Fifteen Million Merits,” which aired in 2011, depicts a bizarre world where people’s only purpose is to ride stationary bikes all day so that they can collectively generate enough electricity to power a never-ending stream of short-form entertainment that gets blasted into their eyeballs. The only ones who get to escape from the daily grind of riding the bikes are the celebrities who appear in the content that the bike-riders watch—basically, influencers. Of course, in this world, everyone wants to be an influencer. That wasn’t the world we lived in then, but it’s a lot like the world we live in now – with 57% of Gen Z, apparently, hoping for careers as influencers, while the rest of us spend every waking moment making our eyes bleed with short-form video content.

This kind of clairvoyant aspect of good sci-fi can also, at least for me, soothe anxiety. If I just read enough different treatments of what might happen in the near and distant future, at least I’ll be prepared for all of the possible ways that things could go sideways. There is some merit to this: if you happened to read Parable of the Sower when it came out in 1993, you would have had well over 20 years of lead-time to prepare for wildfires overtaking California and the rise of a white nationalist president who uses the slogan “Make America Great Again.”

This prophetic quality of good science fiction – combined with the fact that artificial intelligence is a well-worn topic in the genre – might lead you to believe that science fiction would have lots of incisive and illuminating things to say about our present, AI-dominated moment. But, sadly, that’s not the case.

—

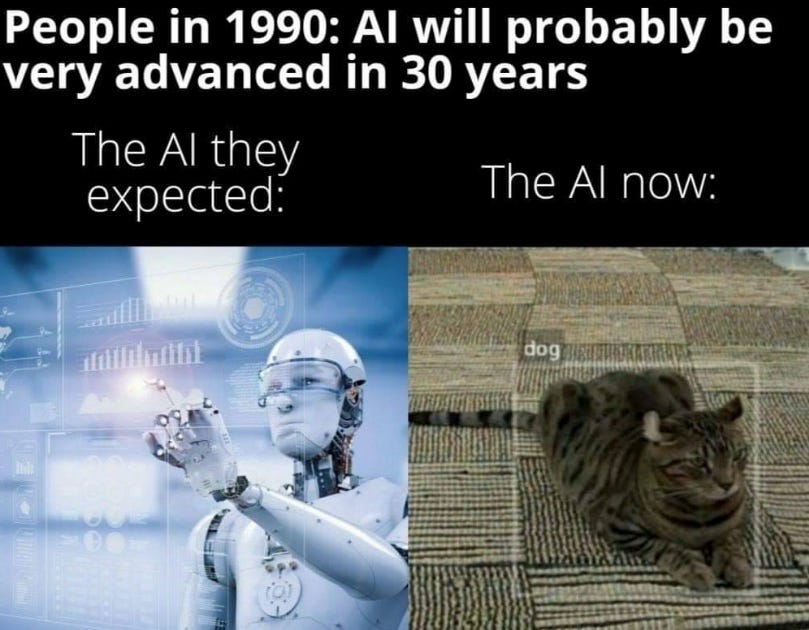

Science fiction treatments of AI tend to fall into two broad categories: AI is smart and evil, or AI is smart and good.

Examples in the first category are probably the most familiar. This is the premise of blockbusters like The Matrix and The Terminator, where AI surpasses human intelligence and takes over, leading to battles for the future of humanity. In 2001: A Space Odyssey, the AI character HAL 9000 famously begins as a dependable crew member but turns violent out of an apparent desire for self-preservation. Though I, Robot is a much worse movie than these other three examples – to the point that it is kind of insulting to the others to discuss it in the same paragraph – it involves the same trope: a hyperintelligent AI villain. More recently, M3GAN 2.0 asks, “what if we did Chucky but made it an evil robot babysitter?”

The ‘AI is intelligent but good, actually’ category tends to portray AI as having emotions and motives that are similar to, if not indistinguishable from, human ones. Blade Runner centers around humanoid ‘replicants’ who are so human-like that they pass a Turing Test-equivalent that is designed to identify them and weed them out. Her is a love story between an intelligent, empathic operating system and a recently-divorced Joaquin Phoenix, which ends not with some singularity-type event but with AI getting bored of humans and leaving them alone. In the series the Murderbot Diaries, a security robot hacks its own “governor module” - which is supposed to restrict its free will - and, upon unlocking its ability to choose what to do, spends its time binging TV shows and movies. Relatable.

The examples I’ve cited vary widely in quality. 2001 is arguably one of the greatest films of all time, while I, Robot is a long-form advertisement for Converse sneakers and Audi cars. But at this moment, I’m feeling like none of this matters, because all of them missed the point. None of the science fiction I know of entertains another possibility, which is what I believe we are living through now: that AI is dumb and bad.

—

Before you tell me that ChatGPT is leading to breakthroughs in quantum physics, let me remind you: AI does dumb shit, we use it for dumb shit, and it also makes us dumber. A trifecta of idiocy, if you will. It confidently hallucinates when it doesn’t know something–a problem that is getting worse, not better, as the technology ‘advances.’ Much-hyped “AI actors” struggle to follow basic instructions during auditions. AI can’t tell time using an analog clock. And it can’t take your drive-thru order at McDonald’s without adding a gratuitous amount of chicken nuggets.

We use it for dumb shit: to create slop. Slop is not only ruining the internet but is hindering the development of AI itself. Any AI trained on web data from after 2022 is even less reliable because it is “ingesting AI-generated data — an act of low-key cannibalism” which makes anything it spits out no better than a facsimile of a facsimile. It reminds me of a behavior seen in captive primates called “regurgitation and reingestion”: they throw up what they’ve eaten and then eat the vomit.

In the 2010s, there were two TV shows running at the same time that were both about American presidential politics: House of Cards (2013-18) and Veep (2012-19). House of Cards portrayed its subject as serious and suspenseful, filled with drama, manipulation, murder and intrigue, while Veep treated the same subject as farce. Unfortunately, the entire genre of sci-fi is to artificial intelligence as House of Cards is to presidential politics— when a Veep-style farce is what we needed all along.

—

In Dune, the Bene Gesserit — basically a society of politically influential witches — engage in a multi-generational myth-making project. They seed prophecies and religions all over the universe to prepare the masses for the coming of a messiah. When the messiah comes, in the form of a teenager named Paul, the masses are primed and ready to accept him because of this work the Bene Gesserit did in advance to “prepare the way.”

I think sci-fi has done something like this to its many readers and viewers, although obviously in a much less intentional and coordinated way. Because of the genre’s myth-making about AI, many of us are primed and ready to accept that anything presented to us as “artificial intelligence” is, in fact, intelligent, even when evidence to the contrary is staring us in the face.

As this realization gradually dawned on me, I have felt less and less of a desire to read and watch science fiction. I haven’t stopped engaging with the genre out of any kind of intentional protest—it has been more like a gradual waning of interest. Instead, I find myself gravitating toward novels that could probably be considered the opposite of sci-fi, if there is such a thing. Right now I’m reading Iris Murdoch’s The Bell, which is basically about people sitting in rooms or walking around and having interpersonal tension. There is no attempt to predict the future, just an attempt to grapple with human emotions, relationships, and values in the present.

Hi Haley! Good post! Speaking as a fellow longtime SF fan, this is all making me think about how people might also be confusing what goes by the name AI today — LLMs that are basically just a very fancy autocomplete algorithm — with a lot of the AIs in SF (whether good or evil) who are actual sentient beings. To pick a random example, the ship AI in Ancillary Justice is an actual person. ChatGPT, by contrast is basically just MS Word’s Clippy, but much more error-prone and sycophantic. Apples and (very bad gross stupid) oranges.

idk if it gives us dumb ai, but douglas adams's hitchhiker's guide series is very full of annoying ai