A few months ago I was chatting with a mom of a toddler who is the same age as my daughter. As tends to happen when parents of young kids get together, the subject of childcare came up. She relayed that she was happy with their current situation — a nanny-share with a few other families — and that it was a welcome change from the day care center they had used previously. One day at their former day care, they showed up at the door and were told to leave: they “didn’t have enough staff for the day and were at capacity with kids.”

My mouth fell open. “You were turned away at the door? For services you paid for? On a day you were supposed to be at work?”

“Yup, that’s exactly what happened,” she said. I relayed that while there were problems with our day care situation — it was expensive, of course, among other things — thankfully nothing like that had occurred in the 9 months we’d been there.

I went home later feeling like we had dodged a bullet: my partner and I had looked at that same day care that her family had used, even putting in an application, but ultimately chose a different one. I wouldn’t say I felt smug, but maybe I was patting myself on the back a bit — that my and my partner’s intuition about that place ended up being right. Turns out the joke was on us.

The history of day care is like the history of oysters: once for poor people, now a luxury commodity. Day cares were originally charity programs, designed to help poor and working class mothers who worked in urban industrial centers. During WWII the US government opened the first government-sponsored child care, to encourage more women to enter the workforce and support the war effort. It was short-lived, ending as soon as the war stopped. It wasn’t until the 1970s, when more middle- and upper-class women began entering the workforce, that momentum began to build around creating universal, nationally-funded childcare programs through the Comprehensive Child Development Act. Nixon vetoed that bill in 1972, stopping the effort in its tracks.

The lack of a universal childcare program has left a patchwork of nonprofit and for-profit services to fill the void, of varying quality and increasing unaffordability. In the last two decades, private equity started making major moves into the sector. Today, 8 out of the 11 largest day care companies in the US are owned by private equity.

There were a number of warning signs before the day I showed up with my toddler and was turned away at the door. A few weeks before, we got a message in the app that the day care used to communicate with families that said they’d be shortening their hours for the coming week because of a staffing problem. It was inconvenient but felt like nothing major: a temporary issue with understaffing that would soon pass.

But the hours were shortened again for the following week. And the week after that.

Then, the “At capacity” messages started coming. The first one came at 10:20am on a Thursday: “Unfortunately, we have reached capacity for children today and will be unable to accommodate any more children.”

The next one came the very next day, even earlier in the morning: at 8:57am. They were so short-staffed that if one or two teachers were out for the day, even due to planned vacation, they’d have to turn kids away.

The message was clear: the earlier you get your kid in the door, the more likely you are to have a spot that day. The next couple weeks we and other parents showed up earlier and earlier to drop off, the small parking lot swarming with cars by 8:30am.

One day my daughter slept in a little late and we got there at 8:45. Too late. One of the managers met me at the door, looking panicked. “I’m so sorry, we have been so busy that we haven’t been able to send a message in the app. We are at capacity for the day.”

One of the primary ways that private equity is able to squeeze profit out of childcare – a historically unprofitable institution – is by maximizing enrollment. The more kids you enroll, the more tuition money comes in. And if you have just enough low-paid teachers to ensure you’re in compliance with state-mandated ratios, you can keep labor costs down. Private equity-owned day cares also try to lower operational costs by, for example, “shifting daily cleaning responsibilities from outside companies to teachers” and reducing “the number of sheets of paper per day” they give to kids. With this model, private-equity owned day cares are able to turn profits for themselves of 15-20%.

While families struggle to afford tuition and day cares struggle to retain their low-paid and overworked staff, CEOs of these companies are, of course, cleaning up: the KinderCare CEO made $2 million last year. Executives at KinderCare are also paid in equity or stock options, where those stock options “accrue depending on how much money the company returns to their private equity owners, Switzerland-based Partners Group.”

Our day care’s staffing issues persisted for months. Like other families we found this totally unsustainable: my partner and I have full time jobs, which is of course why we needed a day care in the first place. While these issues were going on we had to use up vacation days to get off work, and when we couldn’t do that, we had to triage our time so that we kept only our most essential meetings and bumped everything else to other days, making those other days chaotically busy. Of course it messed up our daughter’s routine as well. All of this prompted us to start investigating other childcare options in the area.

But the moment that really broke us happened when my husband was speaking with the daycare’s on-site manager: she let slip that new kids would be starting soon in our daughter’s class.

Despite everything that was going on, and despite the fact that they were barely able to comply with the state ratio of 1 caregiver per 6 children (which is high already - for many friends elsewhere in the country their state ratio is 1 to 4!), they were continuing to enroll more children. It was absurd. The only thing I could think to compare it to was an airline, in that they were systematically overbooking the plane.

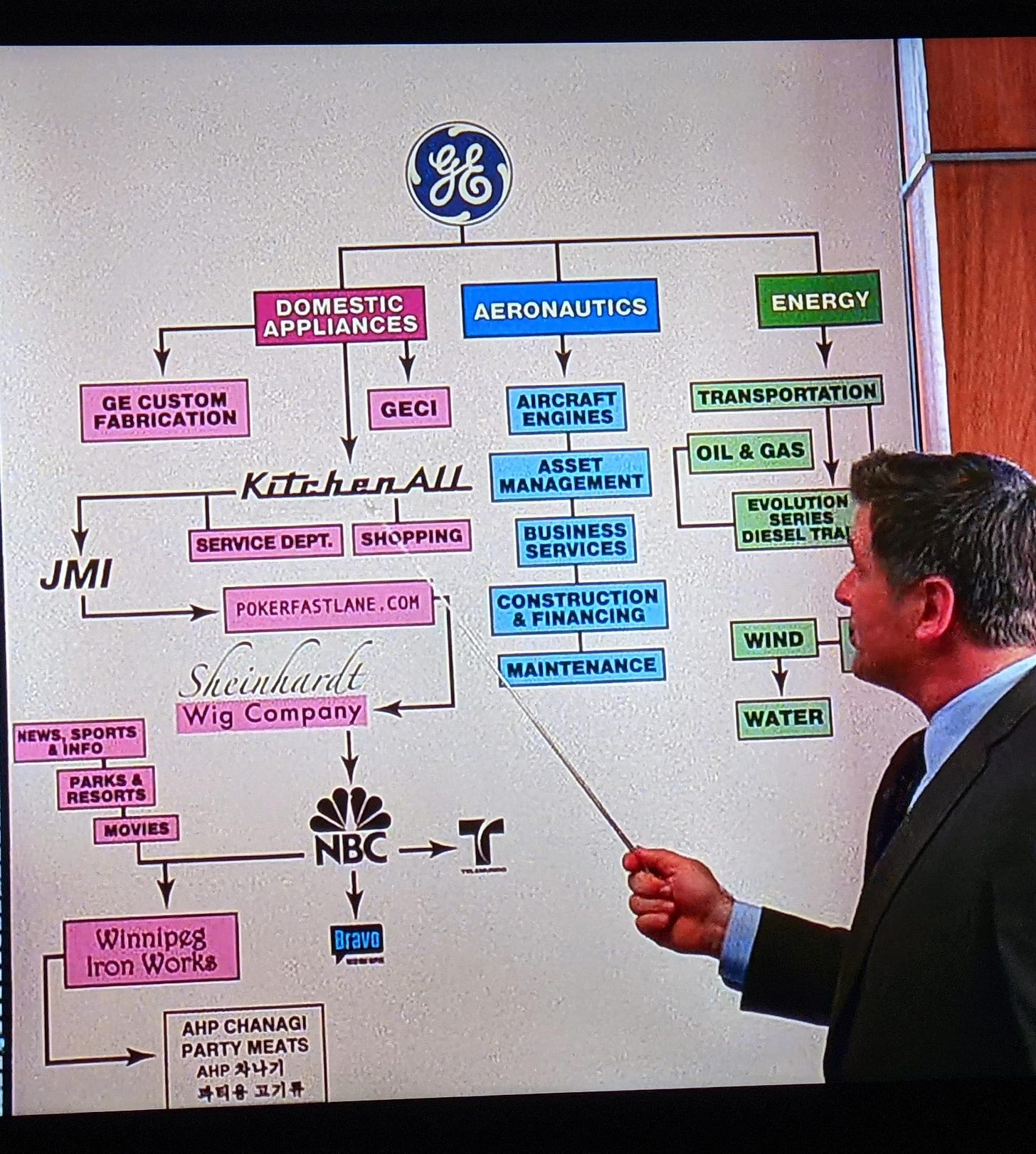

I was shocked that any day care would function like this – I know, I know, probably very naive on my part – so I started some frantic, rage-induced research. I found that our day care is one of many “day care brands” owned by the Learning Care Group. Learning Care Group is, in turn, owned by a private equity firm called American Securities. Apparently American Securities owns many companies, including: Conair, which makes things like kitchen appliances; FleetPride, a parts distributor for the trucking industry; and The Aspen Group, a “leading multi-vertical retail healthcare support organization providing business support services to consumer healthcare brands” (huh?). Quickly I got the impression that charting all of these businesses and their interrelationships would make 30 Rock’s satirical GE org chart look quaint.

But then I looked into other day cares in town. All of the places we had toured and all of the ones that came recommended were, it turns out, owned by private equity firms as well. The only places that we had heard of that didn’t appear to be owned by private equity were church day cares that were only open for half the day and closed all summer. There’s no way that would work for us. We also didn’t have endless amounts of time to look up the ownership situation of every day care in town.

Also, I’m not sure it matters. Despite everything I’ve said so far I think it is at least possible for a child to be safely cared for in a day care that is owned by private equity. Or at least I hope this is true, as our daughter started a new day care recently, and of course it is owned by private equity. The facilities seem nicer and the ratio they have currently of students to teachers in the class is better. We get a small tuition discount because the facility is associated with my partner’s employer and so the total cost is not too much more than our old, unacceptably chaotic, day care.

But private equity companies have a playbook: buy a business, run it into the ground, extract maximum profits, flee the scene. They are responsible for the bankruptcies of many popular restaurant and retail chains: Toys R Us, Red Lobster, TGI Fridays, Bed Bath n’ Beyond — I could go on and on. They’re responsible for elder care facilities imploding and closing down. Knowing this of course leads me to wonder: how much longer will my daughter’s new daycare be an acceptable place to send her for 8 hours a day? It’s very possible — even likely — that it’s a decent place only because we are experiencing it in the early stages of the private equity takeover. And its implosion wouldn’t just be an inconvenience to us as parents: consistency in who provides childcare is critical for her and other kids’ development.

Is there any hope in this state of affairs? Of course, crisis always presents opportunities. As private equity hoovers up more childcare centers, and as conditions deteriorate, it may provide the fuel we need to see mass unionization in the sector. And if parents can unite with child care providers to support their demands — whether for better pay, staffing ratios, etc. — together they could become a major bloc that could take on the shadowy forces of capital ruining childcare provision. (I genuinely have more hope for this possibility than the US government passing a universal childcare bill: no one is coming to save us but us.)

Yet despite knowing this, and despite both adults in our household having fairly extensive knowledge of how to help workers unionize, we pursued an individual solution to our childcare crisis rather than a systemic one. All the time I talk with workers about the reasons why they might consider staying in a job they have issues with and unionizing to improve it, rather than simply finding a different job. But we did that very thing: we cut and run.

On balance I think that decision was justified: we were genuinely concerned about our daughter’s safety in such a chaotic and understaffed environment. And even if the day care providers in the facility were already in the process of unionizing, which we don’t think they were, winning a first contract can sometimes take years. We didn’t want to leave our daughter in a potentially unsafe situation for any longer than we absolutely had to.

Part of why I wanted to write this is that while many of us know on an abstract level that private equity is bad, we don’t really understand how it shows up in our daily lives. Most parents I’ve spoken to in town have no idea that their kid’s day care is almost certainly owned by private equity. And part of how private equity gets away with running their playbook again and again is by hiding in the shadows. So while the timing wasn’t right for us to pursue a structural solution to our own childcare crisis, maybe if more families start to draw connections between issues they experience with childcare on a day-to-day basis and the private equity takeover of the sector, we can lay the groundwork for the system-wide changes that we all desperately need.

I hate this so much!! (not you I like you but this is insane)

What a wonderful and infuriating piece! Minor detail, but I love that initial story about feeling good that you “dodged a bullet.” It’s such a natural response. I feel like we are living in an era where the short-lived relief of “dodging” is quickly quashed once we notice the bullets are everywhere! Here’s hoping that it generates solidarity on a mass scale 🤞